Hurricane Season Reference: The Models Of Interest

Since the weather across the Southeast is pretty much set in place for this week, I think it is a good time to discuss models. Every hurricane season there are a million questions concerning “how good is such and such model?”. The reality is that most models are generally pretty good, all are useful, none of them are close to perfect. They all have assumptions built in to simplify the math to the point the model can run in a reasonable amount of time. This leads to models have certain biases in how they evolve the steering patterns, how they resolve features that will shear a storm, ect ect.

In this post I’ll discuss the models I like to use, their weaknesses, and the importance of ensemble guidance.

All models are wrong but most are useful

I rarely care where a particular model run puts a storm at. The important questions are why does it send a storm where it does and does it strengthen/weaken it? There are other things to consider when trying to figure out the why of a model run.

- Are the initial conditions correct? There are times when a storm is too weak or the model doesn’t have a good handle on a small feature that will have steering consequences.

- What model biases are coming into play? A good example is the Euro tends to be too strong with ridges and the GFS too fast to break them down.

- Is the track sensitive to how strong the storm is?

That’s not an exhaustive list, but these are some of the things I’m considering each and every model run.

The “Global” Models: GFS and Euro are Kings

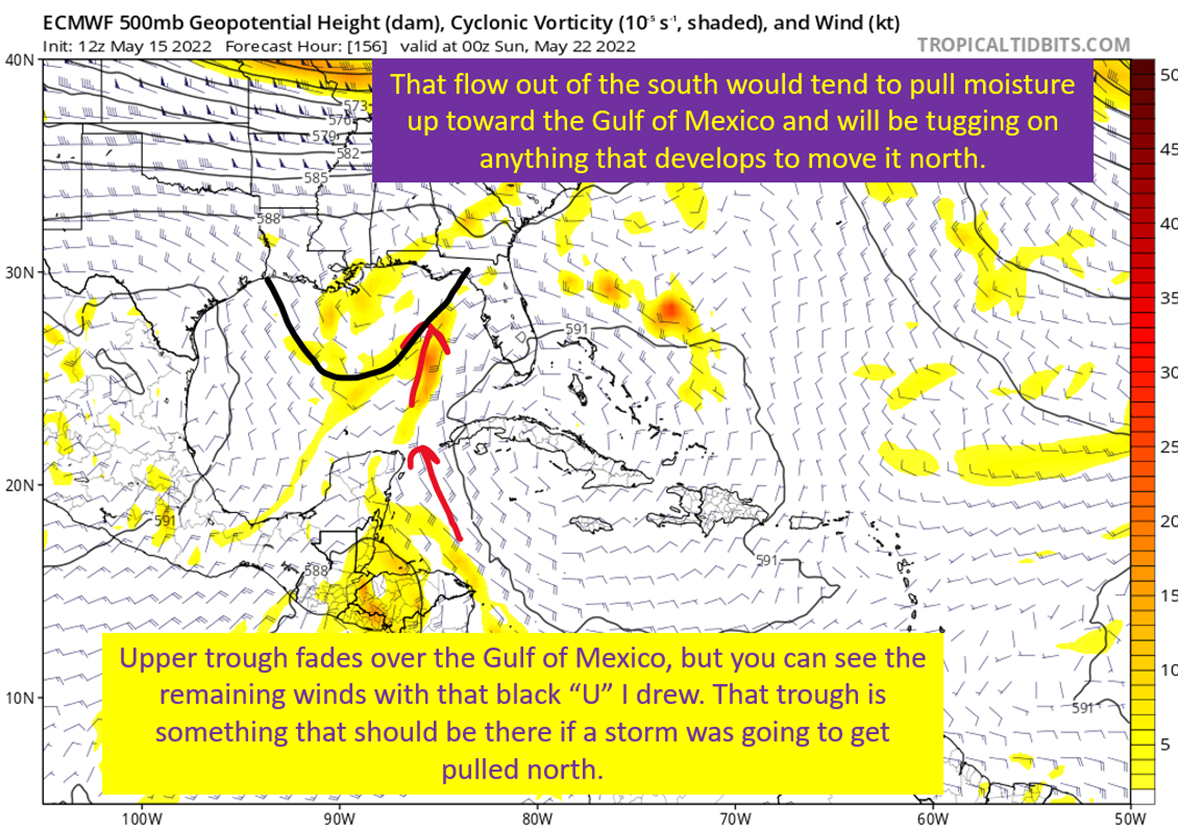

The European and the GFS have the best track record for the large scale stuff that will steer a storm. They again, aren’t perfect but simply tools in the forecaster’s toolbox. I also tend to focus on these models in the 1-4 day range, and worry about the ensembles far more when looking in the day 5+ range. As mentioned above, these models have biases. The Euro has always wanted to make ridges a little too strong and this gives it a west bias generally speaking. Furthermore, it has had trouble with developing systems over the past two years or so.

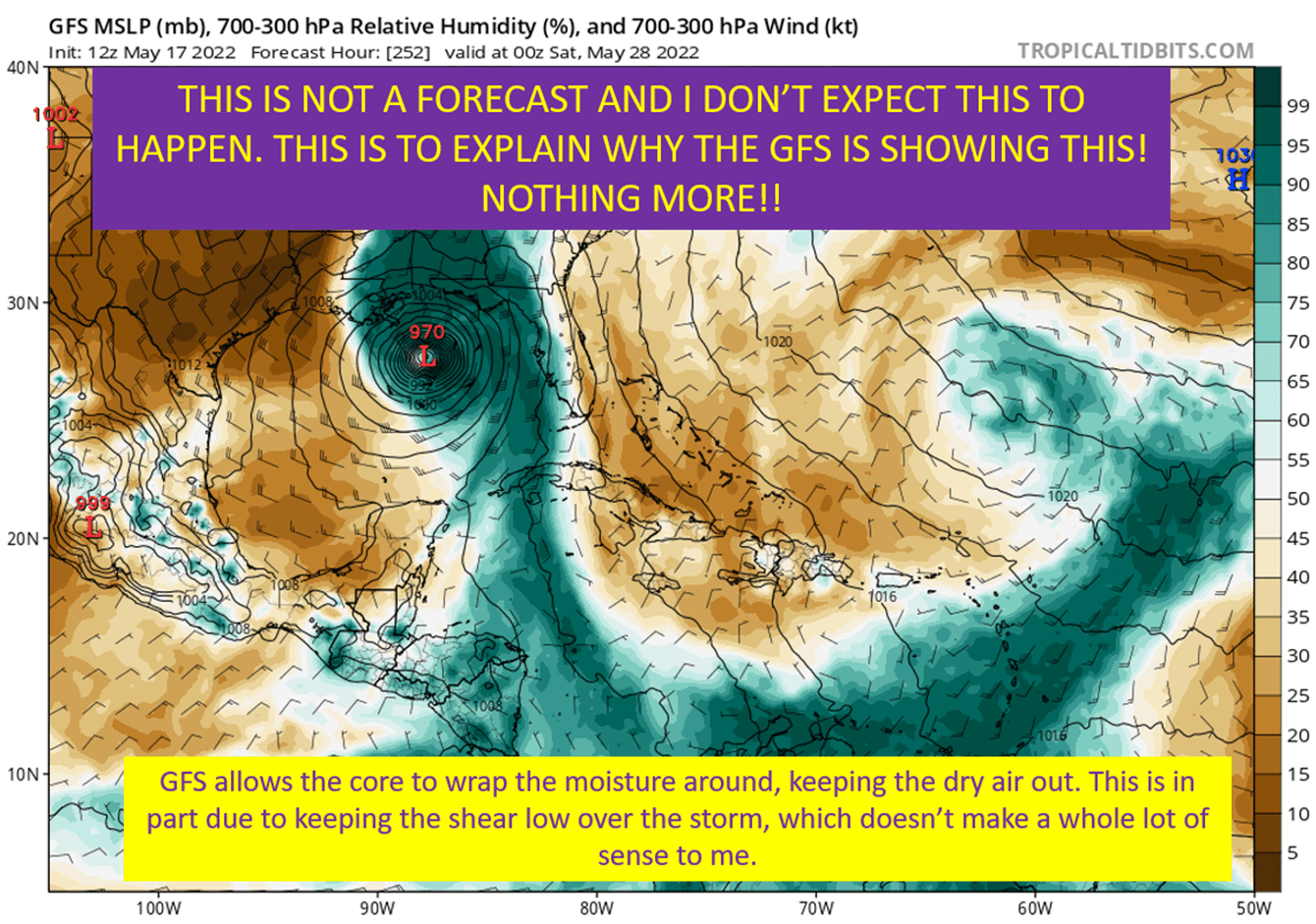

The GFS is the opposite. It is generally too fast bringing shortwaves across and weakens ridges too fast. This leads to it having an east bias generally. In addition, due to how it handles convective feedback, it will spin up many a phantom storm that won’t ever develop.

Other Global Models: UKMet, Canadian, Icon (I guess)

These are also typically sound models, but generally lack the skill of the big two above. The UKMet, in my experience, is probably the best of the rest. I think of these as pieces of an ensemble, helping to depict possible reasonable solutions. Same rules apply when considering their output too. Why is it showing this evolution and does it make sense? This is the question I’m always asking myself.

Always Use Ensembles

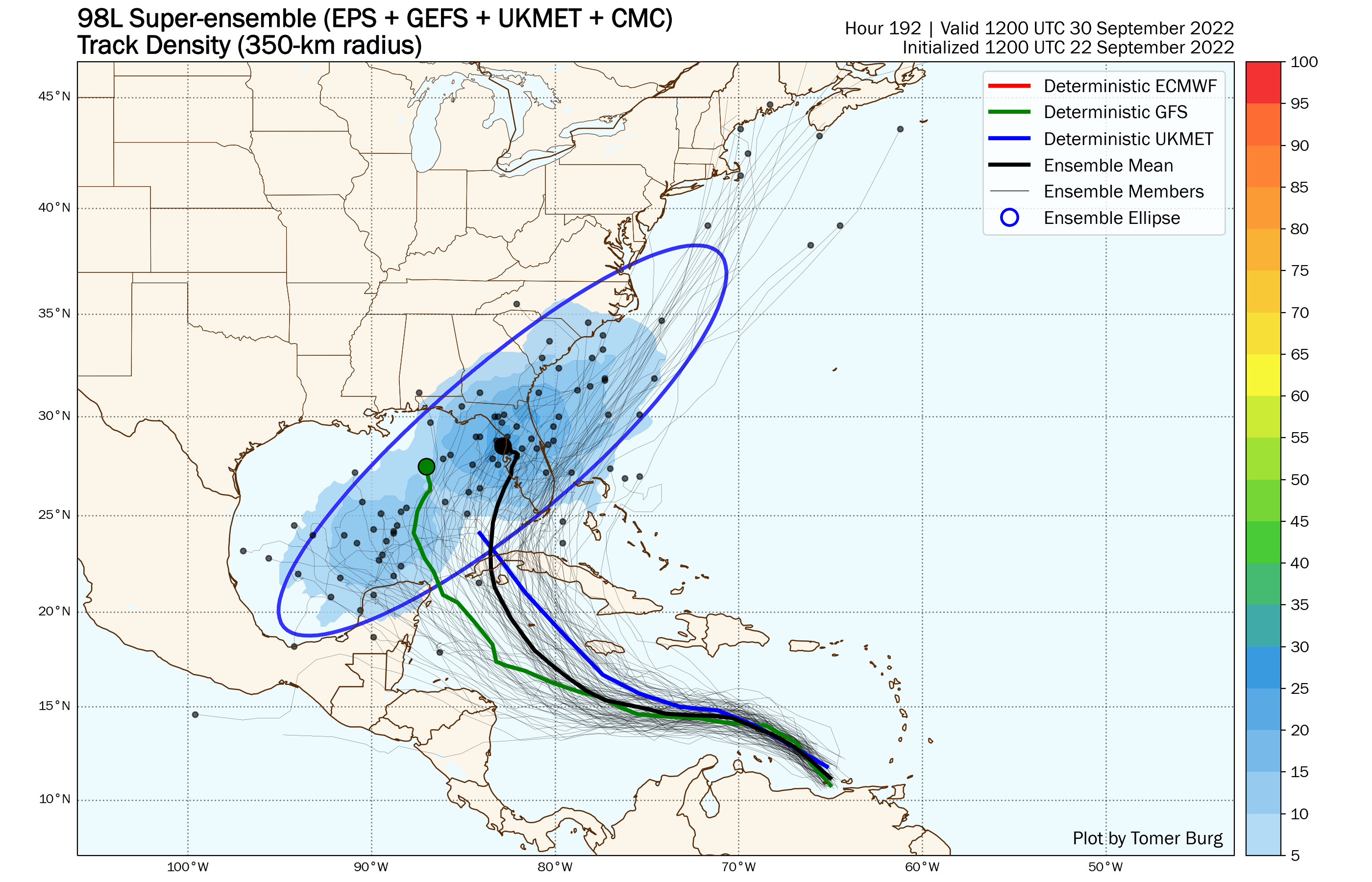

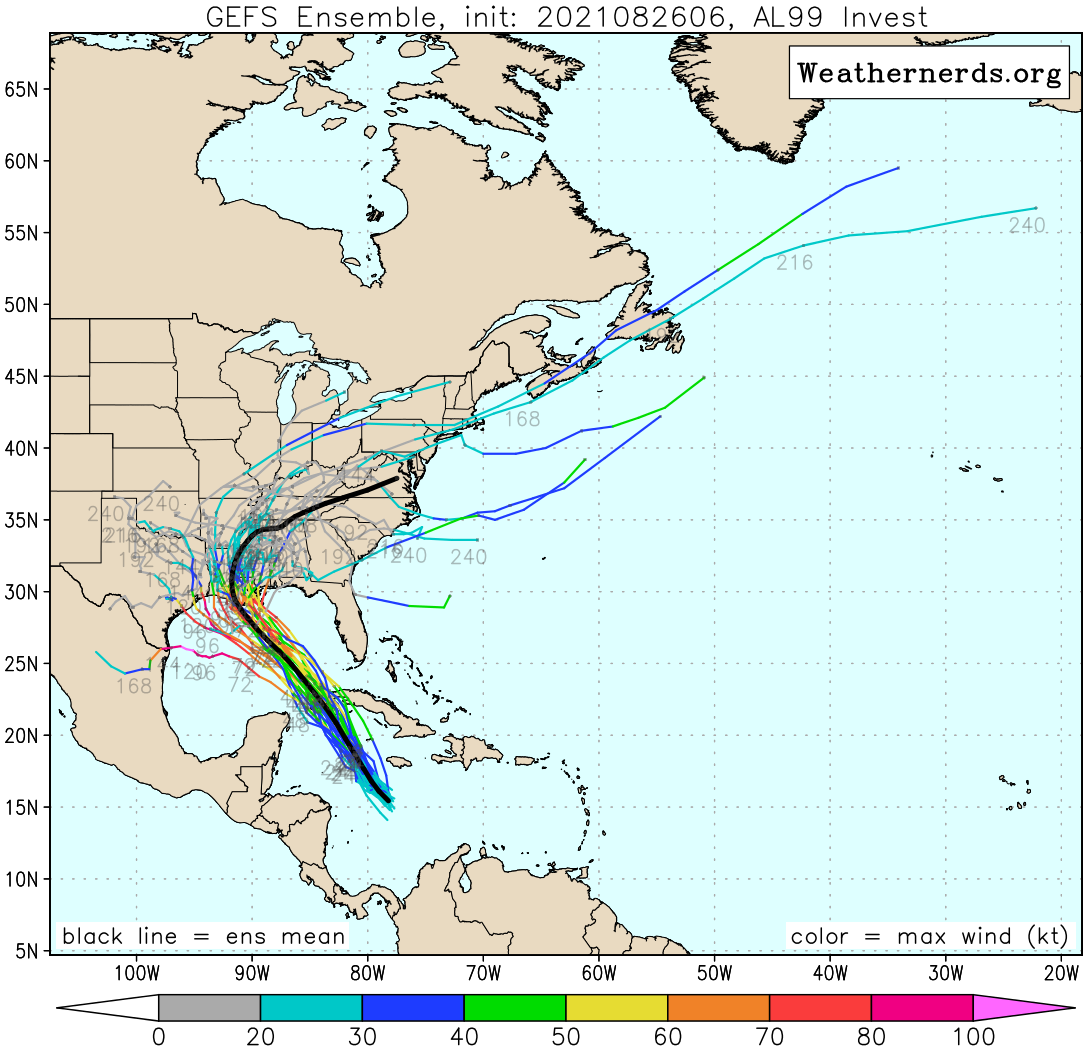

On top of the biases, since each step carries errors from the last on any model, errors tend to compound as the model gets farther out in time. That’s why after the Day 4 (and sometimes even sooner if there’s a lot of uncertainty), I want to use a combination of the GFS ensembles (GEFS) and European ensembles (EPS) to get an idea of the overall spread of possible outcomes. Of course, this doesn’t mean the combination of those ensembles gives you the actual spread of possibilities.

The European has 50 members and is sometimes too dispersive with the possible outcomes. Also, even with 50 members I’ve seen it be underdispersive (Laura 2020 is a good example). The GEFS has fewer members and I haven’t found it to keep too wide of a spread (yet) but a forecaster still has to consider if an individual run doesn’t have too small of a spread.

Hurricane Models: HWRF and HMON

With these two I will pay attention to where they send a storm, but my primary concern how they evolve the structure of a storm and deal with intensity. The HWRF has been extremely good over the past couple of years, in my experience. Look, intensity is still very difficult to get correct but the leaps the HWRF has made in terms of getting the structure right often gives incredible insight into what should play out.

The HMON, while I’ve found it not quite as good, is still helpful in terms of structure and I remember it being the first to get the right idea on Sally’s path in 2020. It might have some extra skill relatively to others when the steering gets really weak, but I don’t have data to back that up. The point is, it can give another data point to suggest strengthening or weakening and explanations as to why something will happen.

Mesoscale Models: HRRR? Yes. NAM? NO! Bad!

The “convective allowing” or mesoscale models are intended for short range when a storm is approaching the coast. The HRRR has been pretty good, in my experience, at catching those last minute wobbles and strengthening/weakening trends. The other thing I like it for is the rainfall forecast. The convective allowing models will show if particularly intense rainfall is on the table and the potential for inland flooding. That is true both for the HRRR and the NAM, but as you can guess from this section title, the NAM has some deficiencies with tropical systems.

The main problem being that the way it handles convective feedback leads to it over strengthening hurricanes to an absurd degree. Well developed hurricanes it will end up bringing to shore as sub-900 mb Category 5 monsters. This means you discount the higher end rain totals until the storm is decaying on land, and flat ignore the intensity presented by the model.

Friends don’t let friends share the NAM during an approaching hurricane.

If You Show A Model At >240 Hours Out, God Kills A Puppy

Save the puppies and don’t share every time the GFS has a hurricane in two weeks. It physically hurts me. It kills cute little doggies. Stop it.

tl;dr version

Models are tools that help the forecasters figure out what should happen with a storm. They are all used together with the meteorologist’s understanding of the physics involved to narrow down possibilities and produce the best forecast possible. I get the desire to look at every model run and get sucked up in the discussion of what each shift in track means. Just don’t take them literally, because they’re going to change. This post is to give you some guidance on which ones are good at what and to you know, temper the “OMG GFS says this!”.